THE WORTHINGTON DIAMOND MINE IN SOUTHWEST ARKANSAS, USA

The Worthington Diamond Mine

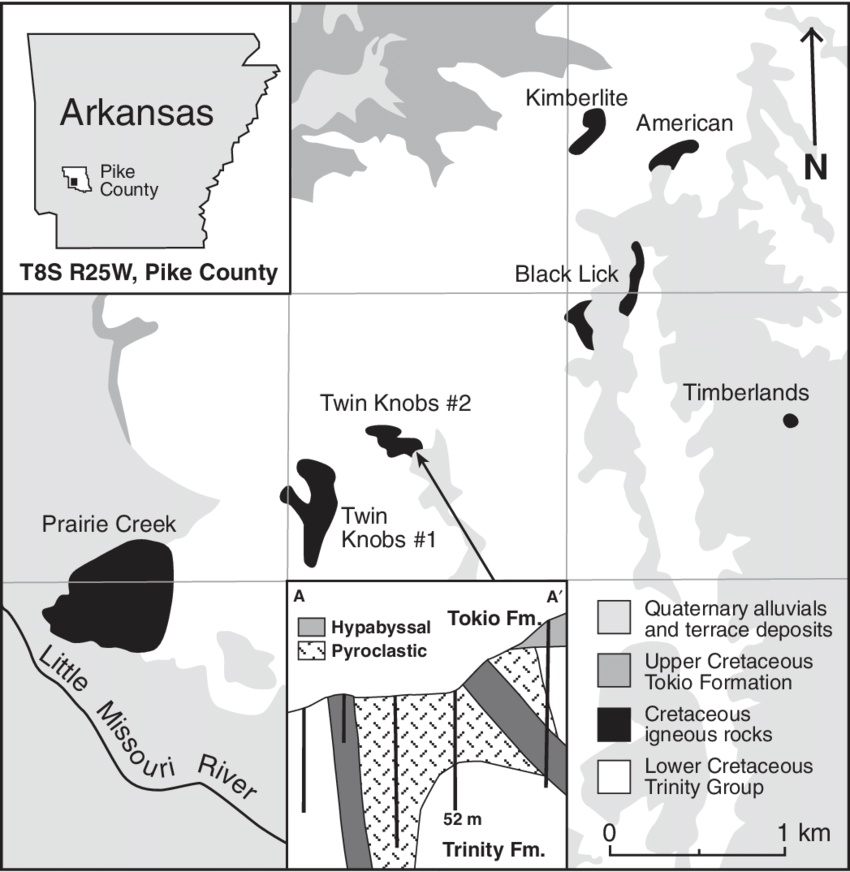

There are eight, known, volcanic, diamond-bearing pipes in the state of Arkansas. All of them are located within three miles of each other in Pike County, which is in the Southwestern corner of the state. The most famous of these igneous vents is The Crater of Diamonds which became a state park since 1972. Visitors are allowed to search for naturally occurring diamonds and keep the ones they find. This unique, state park has hosted between 100,000 and 200,000 visitors each year since 2007.

The diamond-bearing pipe that is closest to The Crater of Diamonds State Park is called “Twin Knobs One.” It is named after two, nearby hills, and is less than one-half mile from the public park.

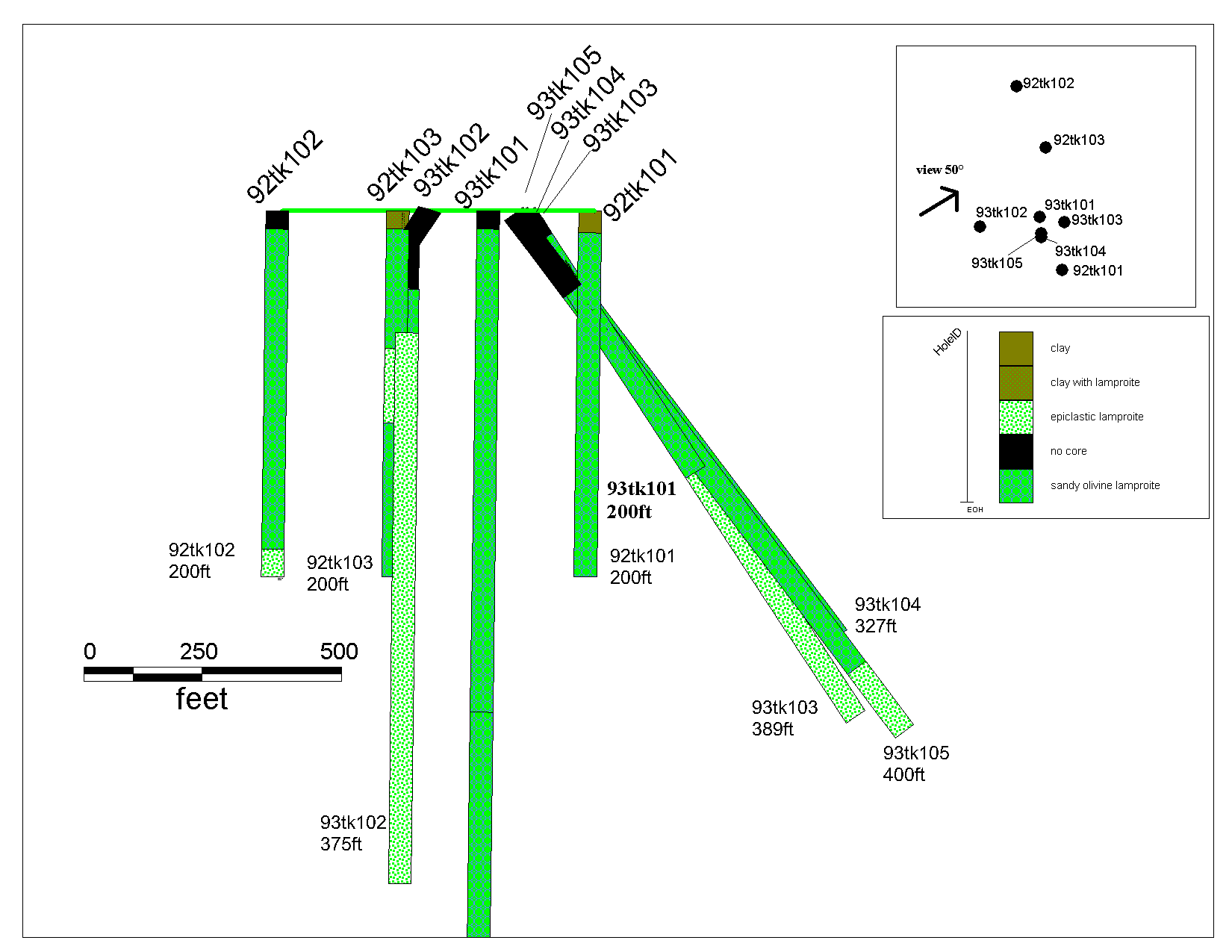

The Worthington Diamond Mine is a ten-acre plot that has one acre of this diamond-bearing, volcanic ore on that property. (One acre is a approximately the size of a football field.) It appears on the map below as the green square with the blue, Twin Knobs One property bordering three sides. This diamond deposit has been core drilled and is known to extend over 200 feet deep. Therefore, it extends as deep as a 20-story building is high.

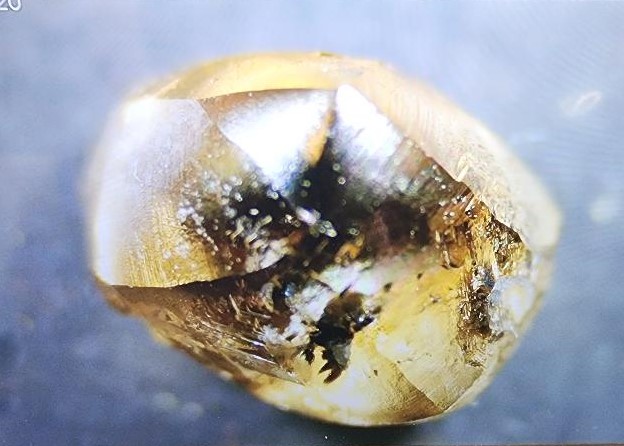

Worthington Mine and Diamonds

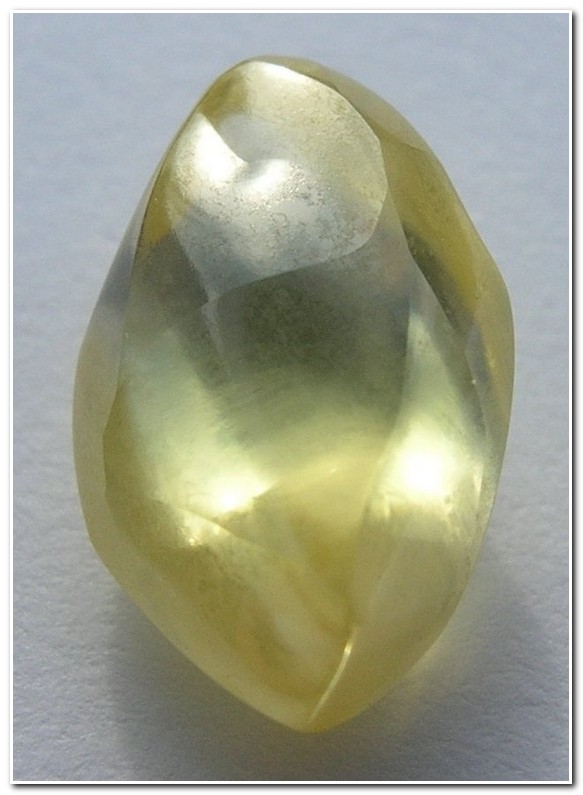

All three of the classic, diamond indicator minerals have been found at The Worthington Diamond Mine as well as diamonds, just like the nearby Crater of Diamonds State Park. Those three, diamond indicator minerals are: 1) black, lustrous, opaque, chromium spinel, 2) red and purple, lustrous, translucent pyrope garnet, and 3) green, lustrous, translucent, chromium diopside. White (clear), yellow, and brown diamonds have been found at The Worthington Diamond Mine just like at the nearby state park.

Ancient Hisotry

Eons ago continents drifted, collided, and buckled up once flat-lying rocks and created the Ouachita (pronounced “Washita”) Mountains. The continents drifted back apart and left a deep-seated rift. Later, earthquake faulting along that line allowed volcanic material to burst to the surface at possibly twice the speed of sound from between 93 and 466 miles deep. This molten, igneous material brought diamonds to the surface where it met a shallow sea. After cooling, this volcanic material was eroded by rains and tidal action. Beach gravels and clay were deposited on top of the diamond-bearing, volcanic deposits in southwest Arkansas where they lay buried and undetected for numerous millenia.

More Modern History

The Riley family purchased 80 acres in 1907, just one year after John Huddleston found the first diamonds in Arkansas at the site that is now called “The Crater of Diamonds State Park.” All of the Twin Knobs One diamond intrusion was on the Riley’s 80 acres of land, although no one knew it at that time.

In 1912, Marion Riley dug a 41-foot-deep well on his land and discovered volcanic tuff all of the way down. Since it looked just like the nearby, diamond-bearing land on the Huddleston farm, he invited Dr. Hugh D. Miser of the U.S. Geological Survey to come out and examine it. Before Dr. Miser arrived Mr. Riley also dug another pit and two trenches for Dr. Miser to investigate.

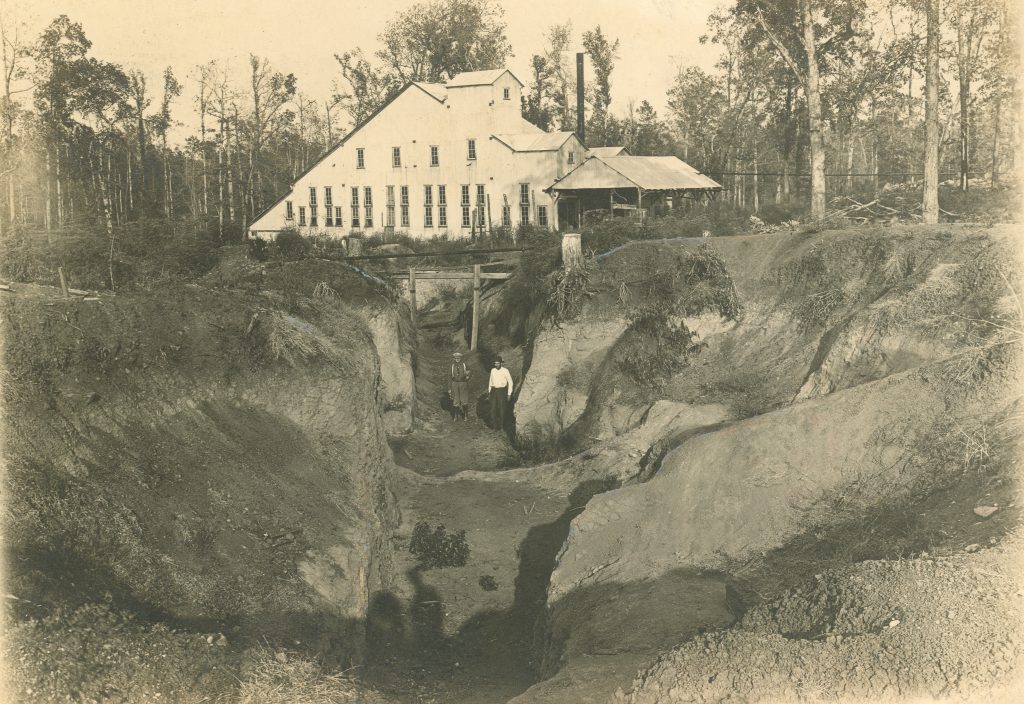

After a close examination of all of the fresh exposures, Dr. Miser declared that it was most likely diamond-bearing, volcanic rock. As a result, one thousand loads of sixteen cubic feet each were dug and hauled to Horace Bemis’ nearby Ozark Diamond Recovery plant for processing. But no diamonds were found. That does not mean the sample did not contain diamonds. It just means that this recovery plant’s process did not find them. During this same period of time lumberman Horace Bemis, who had no diamond recovery experience, was using a log washer to isolate the diamonds in the ore. This method proved to be ineffective at finding diamonds even at the site of the present-day, Crater of Diamonds State Park. That equipment was later abandoned due to its lack of efficiency.

But because of those initial, discouraging results, no additional mining or sampling was done on the Riley farm.

Marion Riley and his wife, Orlean, divided their 80-acre farm into eight, 10-acre plots and gave it to their children on October 12, 1926. Each daughter was given 10 acres and each son received two, 10-acre plots. Six months later, one of the sons decided to trade one of his 10-acre plots for a new car. On April 13, 1927, the land-for-car trade deal was registered at the Pike County Courthouse in Murfreesboro, Arkansas. L. M. Riley and his wife, Snow Riley, were given a new, 1927 Hupmobile by the owners of The Carroll Auto Company, Charley and Nora Carroll and they became the owners of this plot of land. That 10-acre plot would later become The Worthington Diamond Mine.

The Carrolls acquired the land because they believed there were diamonds on it. But they never did anything to attempt mining their 10-acre plot. In 1982, the Carrolls gave the land to their grandson and his wife, Dick and Diane Carroll.

In 1978, Glenn W. Worthington first heard there were diamonds in the USA and that you could hunt for them at a state park in Arkansas. Additionally, he was shocked to learn that people were allowed to keep all of the diamonds that they found. He immediately quit his job and drove to Southwest Arkansas where he lived in a tent for seven weeks and hunted for diamonds. He did not find any diamonds during his first three weeks of labor. Then he found ten diamonds in his last four weeks of diamond hunting. The largest was an imperfect, 1.20-carat brown. His best find was a 78-point (just over ¾ carat) flawless, yellow diamond. He then returned to Kansas, went back to a regular job, and wrote an article that was published in The Kansas City Star Magazine about his diamond-finding adventure.

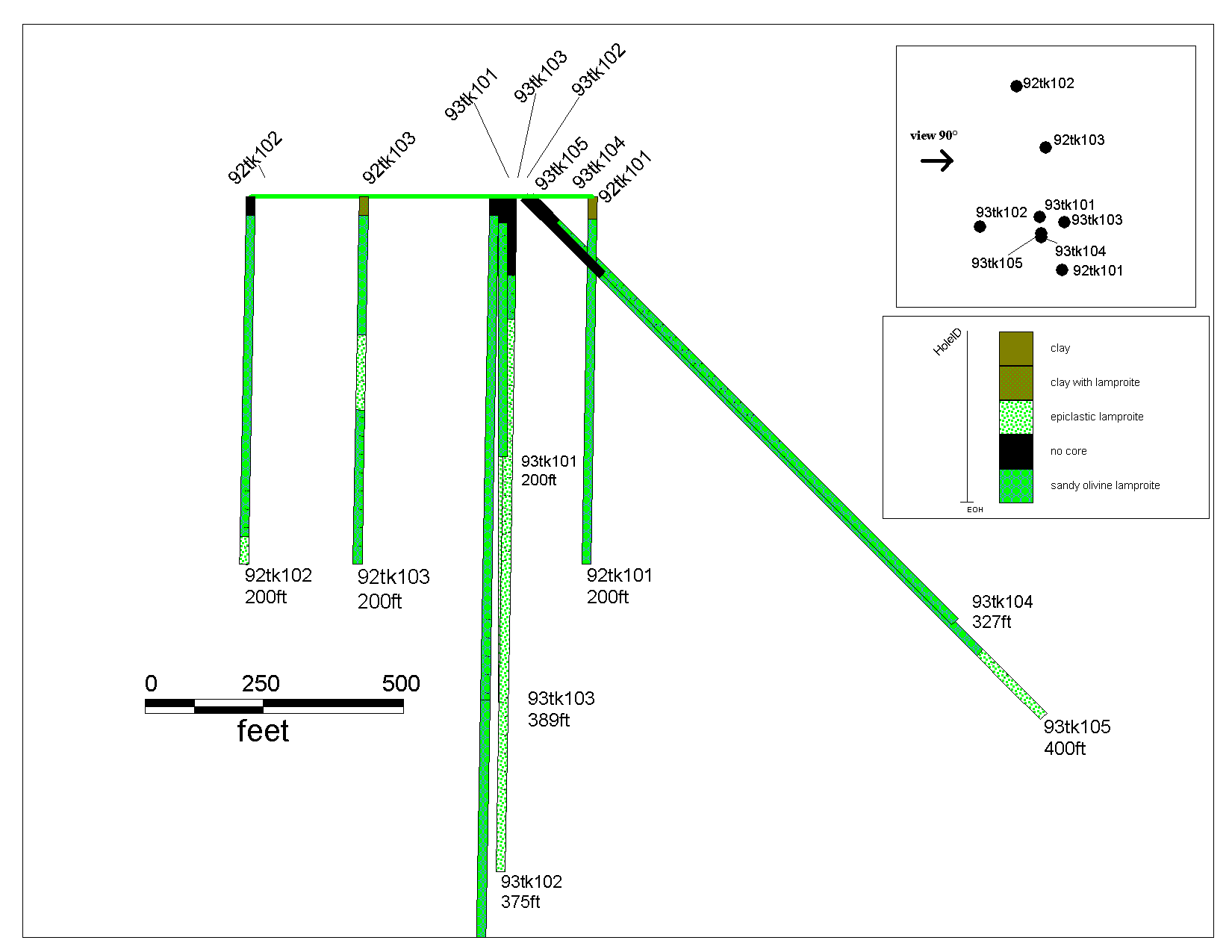

In 1981, Superior Minerals (a division of The Superior Oil Company) leased the minerals rights to Twin Knobs One. At this time the size and shape of this volcanic intrusion was first delineated. Twin Knobs One was determined to be an elongated pipe with two lobes, oriented north-south and covered 12.356 acres. In addition to scientific study of the intrusion, geologist Mike Waldman and other employees of Superior Minerals found a few diamonds at Twin Knobs One. Then, without notice or prior warning, Superior Oil closed down their minerals division and abandoned all of their geologic studies worldwide. This meant that the work Superior Minerals was doing at Twin Knobs One also had to be abandoned despite their successes.

From 1992 to 1994 Texas Star picked up the option to continue the study and diamond recovery efforts at Twin Knobs One. They paid the Riley Heirs $1,000 per week for three years for the right to study their land. And part of the agreement was that the Riley Heirs would be given all of the diamonds recovered during their studies.

Because Texas Star did not have access to the results of Superior Minerals’ extensive, scientific studies they started all of that geologic work all over again. Texas Star’s geologists performed extensive ground magnetic surveys and mapping. They drilled twenty-one holes and recovered thousands of feet of core taken from depth. Some were drilled on 45-degree angles in different directions to help determine the size and shape of the buried, diamond-bearing, lamproite pipe. One hole was drilled straight down ONE THOUSAND FEET!!! It is the deepest hole anyone has ever drilled in lamproite in North America. They stopped drilling at the 1,000-foot depth even though they were still bringing up lamproite core. They decided to cease drilling because it was costing them $40 per foot, and they’d already spent $40,000 on that one hole in the ground.

Texas Star finally decided that it was time to start digging and washing mini-bulk samples of ore taken from thirteen trenches they chose to dig across the 60-acre Riley Farm. The ore was hauled to a nearby, multi-million-dollar diamond recovery plant that Texas Star had imported from South Africa and had assembled on a hillside at The American Mine Site.

In some test pits they found no diamonds at all. But Texas Star did successfully recovered 18 diamonds from their various test holes. The largest diamond recovered weighed 73 points (almost 3/4 carat because there are 100 points of weight per carat). The two, best, test pits were all within 100 feet north of the property line of what would one day become The Worthington Diamond Mine. Nine diamonds were found there. The next best test pit was fifty feet north of those, two, successful pits. They found another three diamonds there. In all, 12 of the 18 diamonds that Texas Star recovered were found less than 150 feet north of the border with the future Worthington Diamond Mine.

Although they were meeting with some success, Texas Star realized that winter was coming and they were afraid the water pipes on their outdoor, diamond-recovery plant would freeze. The company had already spent all of their money studying this site. They realized that they were out of funds to continue their $1,000-per-week lease and expensive diamond recovery efforts. In late December, 1994, an article in the local newspaper announced that Texas Star planned to immediately shut down for the winter and planned to begin operations again in the spring. But the plant was not reopened.

Glenn and Cindy Worthington were married in Overland Park, Kansas, in August of 1994. One year later they quit their jobs, sold their home, and moved to Murfreesboro, Arkansas, where Glenn had found ten diamonds seventeen years earlier. They bought five acres of land directly across the river from The Crater of Diamonds State Park. There they worked together building a two-story, log home, doing most of the construction work themselves. They also opened a business they called “M.A.P./Mid-America Prospecting.” They bought and sold diamonds that were found at the state park.

When they were done building their new, log home, they moved in, and Cindy immediately went to work for The Crater of Diamonds State Park doing rock, mineral, and diamond identification. Texas Star reopened their multi-million-dollar diamond recovery plant, and Glenn landed his dream job as one of the workers operating the plant.

Through special arrangements, 9,600 tons of ore were dug at The Crater of Diamonds State Park and hauled to the Texas Star plant for diamond recovery. Two teams of men worked 12 hours a day, 7 days a week to keep the plant running 24/7. Two hundred and ten diamonds were recovered. As per prior agreement, all of those diamonds were given to the state park. The only thing the mining companies got was information that helped them to decide whether or not they wanted to bid on commercially mining the state park. None of them decided to pursue further diamond-recovery work at the state park.

But since Texas Star (now named Star Resources/Diamond Exploration, Inc.) had its plant up and running again they decided to continue exploring for diamonds in the volcanic pipes outside the state park. Glenn Worthington continued working with them for three years as they did extensive ground magnetic surveys and a core drilling program at the other diamond intrusions known as Black Lick, Twin Knobs Two, The American, The Timberlands, and The Kimberlite Mines. Their biggest project was at the Black Lick Intrusion where they decided to do a HUGE excavation. They spent over $750,000 on a hole in the ground. Then they dug and stockpiled ten tons for starters. Once again, they had spent all their money on geological studies and core drilling and ran out of money when it came to finally start recovering diamonds. After processing just two tons of that stockpiled material, they said they were going to close down the plant and lay everyone off on Friday.

Glenn and his co-workers were told to clean out the office during their last week on the job. They threw nearly everything in the trash. Glenn noticed someone had thrown all of the old, Twin Knobs One core drill and test pit information in the trash. He asked if he could take it home, and permission was granted. That information and maps in those notebooks had cost the company hundreds of thousands of dollars. That proprietary, company information had never been made public. Now, Glenn was in possession of all of that valuable information.

Cindy Worthington had noticed an ad in the local newspaper that some land with a small house on it was for sale along highway 301, not far from The Crater of Diamonds State Park. Curious where this was Glenn and Cindy drove over to see if they could find it. They discovered it was four-and-one-third acres that sat right next to the Riley Farm that had The Twin Knobs One Intrusion on it. This property was immediately down slope from the diamond intrusion, and they figured that some diamonds had washed down and onto this property that was now for sale. On May 25, 1999, they bought the land and the little house that sat on it.

Over the years they dug down to expose a gravel layer on their newly acquired land. They washed a lot of it in hopes of finding a diamond, but never found any.

In April of 2003, Glenn W. Worthington wrote a book about the history of diamonds in Arkansas, and the couple self-published 5,000 copies of it through their business M.A.P./Mid-America Prospecting. He re-wrote “Genuine Diamonds Found In Arkansas” and did another printing of it in June of 2007. Two years later, he did a third update to his book, and the couple had another batch of books printed. Eventually, a fourth edition was printed. He also wrote numerous magazine articles on the topic for various magazines. The editor of “Gold Prospectors” invited him to write an article for their special gem issue. His article was published in the September-October, 2010, issue; and his photo was placed on the front cover.

Glenn worked as a plumber on new construction, commercial projects in Little Rock and Hot Springs but also spent a lot of time digging for diamonds at Arkansas’ Crater of Diamonds State Park. By 2010, he had found 178 diamonds. His largest two were a 2.04-carat, flawless yellow, and a 2.13-carat brown which he had cut to a 1.21-carat marquise that graded out very well.

On December 2, 2011, Glenn wrote a letter to Dick Carroll and asked if he would be willing to sell his 10-acre plot of land that was just 650 feet east of their 4 1/3 acres next to Twin Knobs One. He never received a reply.

On April 14, 2015, he composed and mailed another letter to Dick Carroll to ask if he would be willing to sell the 10-acres that his grandparents had given him after they had traded a new Hupmobile for it in 1927. Again, there was no reply.

On November 20, 2018, Glenn wrote again asking if he could buy the Carroll’s ten acres of land. This time his wife, Diane, told Dick, “Why don’t you at least meet with him and talk to him about it?” Dick told his wife, “Because I don’t want to sell it. My grandparents gave it to me.” She insisted that he should at least invite Glenn over to talk about it because she knew Glenn even though Dick Carroll had never met him.

As a result, Glenn was invited over to the Carroll’s house to present his offer for the land. Those ten acres sat in the middle of pine plantations. They were inaccessible (land locked) in that no roads led to it or from. In fact, to the east of it there were only trees and timber company pine plantations for 13 miles with no houses. That 10-acre plot was hilly and covered with mature trees. Glenn and Cindy had agreed in advance on a generous offer for the property that the couple hoped he would not refuse.

When Glenn presented his offer to purchase the dormant land, Dick admitted he really did not want to sell it. Glenn asked when he had last visited the property or done anything with it. He said he had last gone out there in 1982 when Superior Minerals was studying the Twin Knobs One Intrusion on the adjacent Riley Farm land. Glenn proposed that since Dick Carroll had not even visited the site in the past 36 years he would not miss it if he sold it. Mr. Carroll replied that he believed there were diamonds on that land. Glenn countered that there very well may be but no one had dug there to prove it. He explained that diamonds were not like bread in a toaster that will pop up when they are ready to be grabbed. You have to dig down, pry them out of the ground, and separate them from all of the other volcanic material. And there is a lot of work to that. Dick Carroll acknowledged that was true. Then, in an attempt to end the discussion, Dick said, “If that land is worth what you offered, then it ought to be worth twice that much.”

Mr. Carroll had won! That did end the land sale discussion. Glenn thanked him for agreeing to meet with him to discuss the possible sale, and Glenn left. As he was driving away from the Carroll household, he called his wife, Cindy, with his cell phone . Glenn explained that Dick Carroll wanted twice as much money for the land as they had offered. He fully expected Cindy to say, “Okay, at least we know and won’t be wondering about that any more.” But, instead, Cindy told Glenn, “If that’s his price, tell him we will pay it.” Glenn nearly dropped the phone and drove off the road. He was not expecting that kind of response from his wife at all. But he immediately turned his truck around and went back to the Carroll’s house.

When Glenn knocked on the Carroll’s door, Dick opened it and had a truly shocked look on his face thinking he had previously told Glenn something that would make him go away and drop the subject for good. Instead, Glenn told Dick Carroll, “My wife said we will pay you your price for that ten acres.” The look on Mr. Carroll’s face was priceless. He did not want to sell the land that had been in his family for 91 years even though he was not doing anything with it. But he had offered a deal, and he would stand by it since the Worthingtons had agreed to his price.

On December 27, 2018, both couples, the Worthingtons and the Carrolls, went to the local title company, and the land-for-cash transaction was finalized. The ten-acre Hupmobile land with the one-acre of diamond-bearing lamproite was now officially The Worthington Diamond Mine.

The Worthingtons then met with the Riley Heirs and signed a mutual, driveway agreement. This allowed the Rileys access from the highway to their otherwise landlocked 60 acres of land. They would be allowed to drive across the Worthington’s 4 1/3 acres; and, in turn, the Worthingtons would have access to their newly acquired 10 acres by crossing 650 feet of the Riley’s 60 acres. The agreement was signed, notarized, and filed at the courthouse.

When the land dried out enough after the winter and spring rains, the Worthingtons purchased numerous dump truck loads of rip-rap and road gravel and had them hauled in and dumped. Then, a bull dozer operator was hired to make the new, 650-foot access road across The Riley land to the new Worthington Diamond Mine.

In June of 2019, a timber crew brought in their heavy equipment including a sawhead, skidders, a delimber, and haul trucks to cut and remove all of the trees from their ten acres. This was like unlocking the lid to a treasure chest. No one could access the gems below the lid until these mature trees were harvested and removed.

After all of the trees were cut and removed, the Worthingtons hired a bull dozer to pile the limbs and forest debris in huge rows. Then Glenn burned it all.

At the same time the Worthingtons had a 5-ton-per-hour diamond recovery plant shipped to Arkansas from South Africa. They assembled it, had a new power pole and electric meter set then had an electrician wire everything properly. They had a supply water pond and a settling/return water pond dug. Then they installed all of the necessary pumps and piping. They planned to capture and recycle rain water to use in their diamond recovery process.

The Worthingtons studied the treasure maps that Glenn had rescued from the trash many years earlier. It was decided that the best place for them to start digging was near their property line with the Rileys next to where Star Resources had the most success finding diamonds.

One of the great unknowns was the amount of overburden. How much alluvium had washed in and settled on top of the diamond-bearing ore. If there was a lot, a large hole would have to be dug just to reach the pay dirt, and that would greatly increase the cost of their mining operation. They borrowed an old backhoe from a neighbor and started digging. After removing a mere three feet of soft, overburden dirt, they hit hard, volcanic rock. What a relief for them! The top of the diamond deposit was not deep after all.

In the fall of 2019, the Worthingtons began hauling diamond ore 1,000 feet from their open pit mine to their state-of-the-art diamond recovery plant. Right away they began finding all three of the classic, diamond-indicator minerals in their concentrates as well as diamonds themselves.

A series of three locked gates were installed along with surveillance cameras and security lights.

With the approach of cold, wet, winter weather they shut down their diamond recovery equipment and drained everything so that the pipes, pumps and equipment would not freeze and break.

In May of 2020, the Worthingtons had their diamond recovery operation up and running again. It was decided at that time that they would no longer make their diamond finds public news so that they would not unintentionally encourage trespassers and diamond poachers.

As the open pit mine got larger, the Worthingtons had a drainage ditch dug so it would gravity drain. Once completed they no longer had to pump rain water out of their diamond mine.

In 2021, the Worthingtons launched their YouTube Channel “Genuine Diamonds in AR.” They showcased their mine excavation work and diamond recovery equipment. Their most popular video has had over one million views.

In October, 2021, the Worthingtons decided to offer boxes of their unsearched diamond ore for sale. They would fill USPS Priority Mail boxes with as much diamond ore as the boxes would hold and mailed them out. “If it fits, it ships” turned out to be an advantageous slogan for the Worthingtons. Their offer was well received. They mailed boxes of their unsearched diamond ore into all fifty states. Box customers began emailing them photos of the diamonds they had found. Among them were some small, pretty, yellow diamonds. The largest finds reported back were a 62-point and a 1.23-carat brown diamond.

The Worthingtons continued excavating and processing their diamond ore through their state-of-the-art, diamond recovery plant in 2022 and 2023. But during the summer and fall of 2024 they incorporated a different plan. They wanted to expose the back side (the east side) of the volcanic intrusion. They wanted to see and study what the side wall of the volcanic material looked like. No one had ever done that before. Mining companies always spent all of their time and money excavating just the pay material.

It took months to remove hundreds of tons of clay and chert to expose a 10-foot-high wall. Then, the cold and wet weather of winter 2025/2025 set in.

In May of 2025, the Worthingtons plan to excavate and process all of the tons of lamproite ore in that contact zone wall that stands as a monument to the violent intrusion that occurred there eons earlier.

If you would like to have a box of unsearched Worthington Diamond mine ore mailed to you, please follow this link: https://diamondsinar.com/product/22-pound-box-of-freshly-excavated-unsearched-diamond-ore/

Please follow this link, and you will be able to choose from a long list of videos that show The Worthington Diamond Mine and their state-of-the-art, diamond recovery plant:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLm-EcKNp5h9nr-tQiDloRXwShlfiGVtBW

Please check out our Facebook page:

References

Hugh D. Miser, Clarence S. Ross, and Lloyd W. Stephenson (1928) “Water-laid Volcanic Rocks of Early Upper Cretaceous Age in Southwestern Arkansas…” U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 154, pages 200 & 201

Glenn W. Worthington (2003) “A Thorough And Accurate History of Diamonds Found in Arkansas” pages 38 & 39

Waldman, Michael A., McCandless, Tom E. and Dummett, Hugo T. “Geology and Petrography of The Twin Knobs One Lamproite, Pike County, Arkansas.

Glenn W. Worthington (Sept/Oct, 2010) “Hunting For Big Diamonds In Arkansas” Gold Prospector Magazine. Pages 20-26 & 38